I've been getting a lot of feedback over the past few days on last week's foray into the world of science. I've been relieved to find that it has been overwhelmingly positive on the whole and it's certainly brought a lot of new traffic to the blog. But nothing is ever perfect and I have also received some constructive criticism, which is always welcome. One such criticism was that I need to be careful of my tone, I mustn't give the impression, for example, that I think people who disagree with me on certain topics are idiots.

To be clear, I absolutely do not think that. There are any number of reasons why some people hold different views to other people and that they are idiots is only one of them. Don't get me wrong, there are plenty of idiots out there but there are also lots of people who just haven't given any great consideration to many topics, or haven't had the benefits of a mainstream education, sometimes there are topics where the evidence doesn't clearly point in one direction or another and we just have to wait for more data to come in before we can be certain (this does not include ghosts or astrology), and there are also people who have grown up in a culture where they have been encouraged to think things which are not necessarily, shall we say, accurate? But when I write this I have a certain audience in mind. I'm not looking to convert true believers into atheists, I don't want to have to explain to someone why the apparent position of balls of plasma light-years away doesn't have an effect on the personality of humans on our rocky planet; I'm speaking to people that believe the Earth is billions of years old not thousands, that all life evolved from one common ancestor and that bacon sandwiches are awesome. My writing about photography has always been aimed at people who are interested in an honest portrayal of the natural world we inhabit and the societies we have created within that, I don't see my science writing as being any different to that.

One thing I will say is this; never take my word for anything I write here. Have a think about it, question it, do your own research into the topic, ask yourself if it sounds likely and what mechanism might be behind it. I am more than capable of making mistakes, mistyping, or getting completely the wrong end of the stick. I would encourage you to take this approach whenever anyone tells you anything; always try to think critically, you'll learn a lot about the subject at hand but also about yourself and the people you interact with.

One thing I will say is this; never take my word for anything I write here. Have a think about it, question it, do your own research into the topic, ask yourself if it sounds likely and what mechanism might be behind it. I am more than capable of making mistakes, mistyping, or getting completely the wrong end of the stick. I would encourage you to take this approach whenever anyone tells you anything; always try to think critically, you'll learn a lot about the subject at hand but also about yourself and the people you interact with.

Having established as much, though, there is still a lot of scope for frustration and disagreement. My natural inclination is to focus on the detail of any given topic whereas other people might like to speak in broader, more general terms. Those people find my way of arguing to be overly narrow and pedantic whilst I find theirs loose and woolly to the point of being meaningless. But imagine you had another way of seeing the world altogether. What if you could smell colours or hear printed words? What if you could taste the days of the week and see numbers that people spoke to you? Such people do exist. They are called synaesthetes (SIN-iss-teets) and are affected by the condition synaesthesia. Literally this means 'joining of the senses' and it's actually a pretty good description of the condition. Some people will taste words; others hear colours; others will see spatial representations of sequences, for example, they'll see the numbers 1-10 running left to right in front of them, 11-20 will run upwards, 21-30 will be over their left shoulder and so on. Over 60 different manifestations have been reported.

When Franz Liszt first began as Kapellmeister in 1842, it astonished the orchestra that he said: 'O please, gentlemen, a little bluer, if you please! This tone type requires it!' Or: 'That is a deep violet, please, depend on it! Not so rose!' First the orchestra believed Liszt just joked; more later they got accustomed to the fact that the great musician seemed to see colours there, where there were only tones. One of my favourite physicists, Richard Feynman, is quoted as saying, 'When I see equations, I see the letters in colours – I don't know why. As I'm talking, I see vague pictures of Bessel functions from Jahnke and Emde's book, with light-tan j's, slightly violet-bluish n's, and dark brown x's flying around. And I wonder what the hell it must look like to the students.'

Whilst not all synaesthetes become legendary composers or Nobel Prize winners there certainly isn't any great cause for concern. Whilst seeing sounds and hearing colours can be distracting to young children initially it seems that the vast majority of those affected grow to use it to their advantage and consider it a blessing; if they've even realised that not everyone senses the world in the same way that they do, that is. Depending on the form the synaesthesia takes it can help with mathematics, time management, better memory recall and other such tasks. I'll try to explain how shortly.

It looks clear now that there is a tendency for synaesthesia to run in families but no specific gene has thus far been found. Also, it doesn't tend to be passed on from father to son and so there has been speculation that whatever genetic components are involved may be on the X chromosome; however, 2 cases of father-son transmission have now been documented. To me this suggests that it is likely to be a polygenic disorder i.e. caused by more than one gene. Whilst this means there are more targets to be found the reality is that polygenic disorders are notoriously difficult to pin down; examples of well characterised polygenic disorders are rarer than unicorn tears. It should be noted that the form it takes isn't passed on, a mother who tastes colours might have a son who smells words - not a sentence I ever thought I would write.

How exactly this phenomenon comes about is not precisely known at present. For a long time it was thought that it was a simple matter of 'leakyness'; e.g. visual signals stimulating the auditory cortex. The electrical signals caused by stimuli that would normally be interpreted in one part of the brain were just spilling over into adjacent areas; but this doesn't really hold together as parts of the brain that become mingled aren't necessarily next to each other. It appears as though there are structural differences in the brains of synaesthetes; there is good evidence that they have more grey matter than the average and that there are more physical connections than the average between their neurons, not just between the sensory areas but generally throughout the brain. There is also increasing amounts of evidence that higher level brain function can be brought to bear on the phenomenon. New associations can be learnt and applied to previously unknown situations; for example, people with grapheme-colour synaesthesia (the most common form) can be shown an alphabet they have never encountered before, like the glagolitic, and learn a completely new set of links between colours and the symbols. This process can be both organic and directed and can happen in less than ten minutes. This would suggest that several separate systems are all involved in synaesthesia and is another excellent example of the plasticity of the human brain.

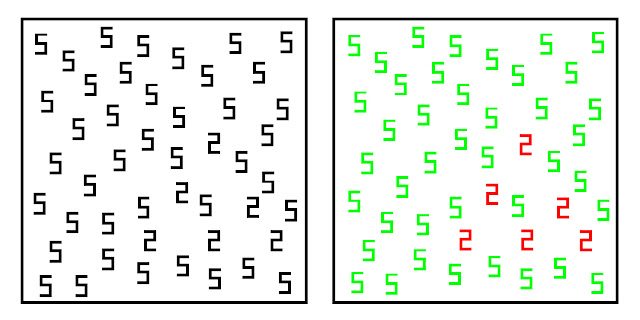

I mentioned earlier that being a synaesthete can have it's advantages, let's look at a few examples. Look at the picture below, try to look at the picture on the left first. Not very interesting is it? Just a whole bunch of 5s randomly strewn about. The picture on the left is a little more interesting, it is identical except that colour has been added. All of a sudden it is very apparent that it isn't just a mass of 5s on the page, there are also a few 2s thrown in. You would have eventually spotted that in the original picture if you'd had a good look at it, but it required only a fraction of a second in the next image (admittedly, as red and green were used, colour blind people will have struggled with this one). People with grapheme-colour synaesthesia pick up on the 2s far faster than the rest of us do.

So what practical applications are there for this? Look at this next picture below of some simple sums. We can all do these, they're at a pre-school level, but children tend to grasp colours before they do numbers and those children who also have grapheme-colour synaethesia will have an extra level of association to latch onto that will likely propel them to the head of maths class. If they learn to harness this to it's full potential then maybe that's one way how we get people like Richard Feynman. You may also imagine how Liszt saw the colours of the notes of his composition rising from the orchestra; if you also had an idea of the colours you wanted to invoke as you composed then this could potentially be an extra tool with which to fine tune the piece as compared to those of us who have to just listen very carefully.

The first reference I can find to synaesthesia was in 1880 by the legendary Francis Galton, so we have known about this for quite a while and as awareness of the condition grows it is now thought that as many as 4% of people could be affected, which sounds like a lot, but many don't even realise they are unusual. The question boils down to this: Is this an entirely new type of phenomenon in the brain or merely an extreme form of something very typical? This is a question that crops up time and time again in neurology and hopefully in many cases we will be able to resolve it as we slowly get a handle on what baseline brain activity really is, if there turns out to be such a thing. One final example, look at the picture below. One of these shapes is called Booba (stop giggling) and the other is called Kiki. Decide for yourself which is which. I know which way I went and I can be fairly confident of which way you will go; the jagged shape on the left will be Kiki and the more rounded one on the right will be Booba (stop it). That's how 98% of people assign them.

So is this a very low form of synaesthesia that we all share? Is it a phenomenon that is unrelated but gives a similar sort of outcome? Is it more of a cultural effect to do with the shapes our mouths and lips take as we pronounce the words Kiki and Booba (see me after class) and the way we associate them with the symbols in the picture? The answer is: we simply don't know. But I do know how we'll find out; through careful observation, rigorous application of critical thinking and leaving your preconceived ideas at the door: through science.

For more information on synaesthesia I have provided links to some of the sources I used. Google will also lead you to some of the support groups that exist like the UK Synaesthesia Association.

All images used with permission under the Creative Commons License

http://www.journalofvision.org/content/9/12/25

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18550184?itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum&ordinalpos=2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19028762

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glagolitic_alphabet

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427393.800-is-synaesthesia-a-highlevel-brain-power.html

No comments:

Post a Comment