I've been on holiday in Spain for the last week and internet access has been patchy so I'm taking the rest of the week off. I'm afraid you'll have to find your own science news for two days. Happy hunting!!

People that know me will know I'm a better writer than I am speaker, so this blog is my way of explaining what it is I do with my spare time and why I enjoy it; namely, photography and science. If the two can be combined then all the better. If you would like to see more of my photos, or to purchase any, then check out my website at www.jasonhehirphotography.com If you like what you see then feel free to spread the word on Facebook and Twitter and the like. Thanks!

Thursday, 27 August 2015

Friday, 21 August 2015

Einstein Does It Again

It is often said that scientists are close minded, that they will do anything to uphold the status quo. Anyone who says this has clearly never met a scientist. I promise you, every researcher out there wants to be the one to upset the apple cart and come up with some kind of paradigm shift in thinking that will lead to the immediate recall of all the textbooks. Whilst doing an experiment that repeats or confirms a previous finding is an essential part of the scientific method and needs to be done, it won't set the world afire.

This is the stage many physicists are at when it comes to the Standard Model. The Standard Model of physics is our best guess so far about how the components of matter all come together. It deals with all the sub-atomic particles we know about, their corresponding anti-particles and the four fundamental forces of nature. It works supremely well and has been verified by multiple, converging lines of evidence from different fields of physics. Much of the testing at the Large Hadron Collider has reaffirmed the Standard Model and many there are genuinely disappointed to have not yet discovered any 'new physics' with the most complicated machine ever built by man. The Standard Model has been broadly in place for several decades now and ever since it's inception physicists around the world have been desperately trying to break it. This week another group failed.

In an open access letter to Nature researchers from Japan and Germany report that they have once again shown that protons and anti-protons are completely identical to each other in every way except their opposite charge. They used a device known as a Penning trap to carefully 'weigh' the protons and anti-protons in the most accurate experiment of its kind to date. They were hoping to find a slight difference that would be a deviation from the Model and open up new avenues of inquiry. Alas, after thousands of iterations they found that they were similar to 69 parts in a trillion. They then repeated the experiment but this time to see if gravity affected the matter and anti-matter in different ways. Again, no dice. Whilst it's lovely to, once again, show how much of a boffin Einstein was and how great relativity is, it would have been incredibly exciting to have shown a crack in the edifice and start hammering away at it.

|

| The Standard Model of physics |

Thursday, 20 August 2015

P-Hacking

Today we're going to get a bit meta. Just as important, if not more important, than science is the science of science itself. How do we know if the papers being published every day of the week are of a high enough standard to be trusted and to take human knowledge forward? What proportion of them will turn out to be wrong in time? How much of this is just due to a natural progression of knowledge and how much of it is due to shoddy work that should have been rooted out pre-publication?

I think science has a problem, not a fatal one, but one that it needs to address. It is increasingly the case that journals are only interested in publishing the papers that will get the most headlines and/or the most citations thereby increasing that journal's Impact Factor. Researchers will naturally want to publish in the journals with the highest Impact Factor and may, on occasion, massage things to help ensure they do so. There is increasingly little space for papers with a negative result or replications of previous experiments, both of which are absolutely vital to science but are not sexy or headline grabbing.

The easiest way to get published is to have a statistically significant P-value. Broadly speaking, the P-value is the likelihood that a result in an experiment could have been obtained by random chance and not as a result of whatever theory you might be testing. The smaller the P-value the more likely the hypothesis you're testing is correct. But the problem is that there are lots of different ways to generate a P-value. Different data sets suit different types of statistical analysis and within each analysis there will be certain parameters and limits to set. How and where these limits are set can give very different results perhaps pushing a negative data set just over the margin into significance.

I should say that this can all be done completely innocently. Researchers won't be malevolently thinking of ways to con the world into thinking that they have a real effect when they don't. All of the little decisions that go into designing a research study, of any kind, can be referred to as Researcher Degrees of Freedom (RDFs). Multiple studies have now shown that the more RDFs you have the more likely there is to be significance found in the analysis. Decisions about when to stop collecting data, which observations to exclude, which comparisons to make, which data sets to combine; these all have an impact on the final results. The phenomenon has come to be known as P-Hacking.

The reason I'm explaining this today is because of an open access article published last week in PLOS ONE. In it, researchers from the US Department of Health and Human Services detailed an interesting but slightly worrying observation. What they did was to look at every large study looking at cardiovascular disease conducted at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute between 1970 and 2012. They defined large as costing more than $500,000 per year to run. There were 55 such trials. These were then segregated into those that took place before (30) and after (25) the date in 2000 when it became compulsory to register your clinical trial and specifically what it was going to do before publication.

17 out of 30 studies (57%) published before 2000 had a positive result; but only 2 out of 25 (8%) had a positive result after 2000. No other factors looked at; like corporate co-sponsorship of the work or whether the trial compared against a placebo or an active comparator; made any difference to the figures. This one simple measure, of forcing scientists to register exactly what the parameters of their study would be before publication, seems to have led to a 7 fold decrease in the number of positive trials.

This is, of course, just one study; one study is never proof of anything. This needs to be replicated in multiple data sets by different groups to see if the effect is real. If it is, it could have profound implications for randomised controlled studies the world over. To be clear, if there is a bad scientific article published it will get found out. The scientific method and the peer review process are not fundamentally broken, but a lot of people might waste a lot of time and research money on a dead end and in these straightened times, when the science budget in the UK is at threat of a 40% cut, we cannot afford as a community, as a people, to be led a merry dance on effects that weren't even there in the first place.

17 out of 30 studies (57%) published before 2000 had a positive result; but only 2 out of 25 (8%) had a positive result after 2000. No other factors looked at; like corporate co-sponsorship of the work or whether the trial compared against a placebo or an active comparator; made any difference to the figures. This one simple measure, of forcing scientists to register exactly what the parameters of their study would be before publication, seems to have led to a 7 fold decrease in the number of positive trials.

This is, of course, just one study; one study is never proof of anything. This needs to be replicated in multiple data sets by different groups to see if the effect is real. If it is, it could have profound implications for randomised controlled studies the world over. To be clear, if there is a bad scientific article published it will get found out. The scientific method and the peer review process are not fundamentally broken, but a lot of people might waste a lot of time and research money on a dead end and in these straightened times, when the science budget in the UK is at threat of a 40% cut, we cannot afford as a community, as a people, to be led a merry dance on effects that weren't even there in the first place.

Wednesday, 19 August 2015

Return of the Cougars

An abstract presented at the 100th Ecological Science at the Frontier conference has done an analysis on the reintroduction of cougars to the eastern United States. Puma concolor still roams the western United States but has been extinct in the east for some 70 years; this analysis specifically looked at the financial pros and cons of reintroducing them to their former range.

The cougars main food source would be white tailed deer and the commensurate financial benefit to their reintroduction generally comes from there being less deer. Given that white tailed deer are involved in hundreds of thousands of collisions with vehicles every year, causing 29,000 human injuries and 211 human deaths per year at a cost of $1.1 billion there seems to be a clear area for potential benefit there. Unchecked deer populations have also led to ever greater damage of crops.

The researchers, from the University of Alaska, projected that over 50 years a successful reintroduction would save 53,000 injuries, 384 fatalities and $4.4 billion dollars as a result of lowering deer densities by about 22%. The deer themselves could also benefit. The cougars will be more likely to kill older and/or weaker animals so there will be fewer deer but the population as a whole would be stronger.

Financially then, the benefits seem clear and we should start buying cougars train tickets to Boston forthwith. But will the public go for the idea. The people of the eastern US are very used to being at the top of the food chain, they might not care for the idea of deliberately putting something near their house which could eat their dog, or their child, or themselves. But like with so many things; war, disease, Tory Governments; the fear of something tends to be far greater than the danger posed by the thing itself. Below I have composed a list of things that kill more people in a year than cougars in the US, in no particular order:

- Honeydew melons

- Being in a hot car

- Family pets

- Highschool shootings

- Falling out of bed

- Autoerotic asphyxiation

- Ants

- Vending machines

So, in summary, I say go for it.

|

| Image used with permission |

Tuesday, 18 August 2015

El Condor Pasa

A novel new method is being used to help sustain a wild population of Californian condors: electroshock therapy. No, that isn't a typo. Twice per year all of the 150 or so remaining birds are captured and electrocuted. It isn't just for kicks, however; over the past decade the biggest single killer of north America's largest bird was death by electrocution after flying into power lines. With a 3 metre wingspan they are more than capable of touching more than one wire at once and being killed; touching just one at a time is relatively safe as the electricity has nowhere to go. Since the introduction of the training death by electrocution has dropped from 66% to just 18%.

The next biggest killer is lead poisoning, thought to be as a result of eating carcasses that have lead shot in them after being hunted by humans. The condors seem to be particularly susceptible to lead and so on their twice yearly grounding they are checked over and operated on if necessary to remove shot. Apparently a ban on lead shot in the area has not led to a reduction in mortality.

This all sounds like quite an arduous experience for the birds themselves but it's probably not as bad as it sounds. In the 1980s there were only a couple of dozen birds left in he wild, at which point they were all captured and brought into captivity. Since then there have been a series of reintroductions back into the wild that have been the genesis of today's 150. As these birds were all born and raised in captivity it's more like visiting home than being abducted by aliens.

The program, as reported in Biological Conservation, is working. In the past 15 years the annual mortality rate has fallen from 38% to just 5.4%, a remarkable achievement. Will this be a large enough population to sustain a genetically diverse enough species in the future? Only time will tell. I recently read an analysis by a genetic statistician that said that, given perfect conditions and full control of who breeds with who, it is very tough indeed for a population smaller than 160 individuals to survive, but we'll never know if we don't try

|

| A Californian condor complete with tracking tags in both wings |

Monday, 17 August 2015

Octopus Genome Reveals Secret of Intelligence

Octopuses (not octopi) are incredible; they're definitely the animal I would most like to be melded with in a nuclear meltdown scenario. We all know they have eight legs but did you know they have three hearts? Their blood is blue because they use a copper and cyanide based oxygen transport molecule instead of haemoglobin. They are highly intelligent, capable of finding and remembering a route through a maze. They are exceptionally good at changing not just their colour but also their texture to mimic their surroundings (see video below) and some species have even been observed using tools.

A recent open access article from Nature reports details of the first sequencing of an octopus genome. Contained within the genetic code they think they may have found a couple of clues as to the remarkable intelligence of these curious creatures. Analysis showed that there were two families of genes that had many more members then would normally be found in molluscs (octopuses are molluscs); namely, protocadherins and the C2H2 family of genes.

Before the first draft of the human genome was published in 2000 there was the naive assumption (although reasonable at the time) that the more complex an organism the more genes it must have. Sensible guesses for the number of genes in the human genome were in the range of 50,000-100,000. When it was revealed that we only had about 22,000 it surprised everyone. It turns out, though, that it isn't how many genes you have but what you do with them that counts. One gene can be expressed in many different ways resulting in production of different proteins with slightly different functions; this is how you can get complexity from a small number of genes. To achieve this, though, you need a set of genes capable of manipulating the other genes in such a way; one such group are the C2H2 family.

Protocadherins are involved with developing neurons, the basic component of any nervous system. Mammals are known to produce a large number of these proteins but generally other families of animals do not. Oysters and other molluscs tend to have about 20 different protocadherins, we now know octopuses have 168. This would allow them to develop a much more complex nervous system than they otherwise might; indeed, octopuses have the largest nervous system of any invertebrate.

Finally the researchers, a joint team from Chicago and Okinawa, revealed that they discovered many hundreds of genes that are unique to octopuses. Some of these are known to be involved in the animal's remarkable mimicking ability but the majority remain a mystery. A rich seam for future research, no doubt.

So there you have it, it would seem that several of the amazing abilities of the octopus could be down to genetic factors. Spare them a thought the next time you chow down on some calamari.

Friday, 14 August 2015

Information Overload

Yesterday I had planned to tell you about the paper from the journal Food Policy that I'm going to explain today but I got a bit carried away and had a rant about GMOs instead. Today I promise to stay more focussed.

To business, then. A few months ago researchers from the University of Florida wanted to see how providing scientific information changed people's minds on scientific matters. What they did was take a measure of people's opinions on several topics such as climate change and genetically modified foodstuffs. They were then provided with statements from scientific organisations like the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Examples of statements used are:

'To date, no adverse health effects attributed to genetic engineering have been documented in the human population'

'The scientific evidence is clear: global climate changed caused by human activities is occurring now, and it is a growing threat to society'

They then polled them again to see if and how their opinions had changed. On the matter of GMOs at the outset 32% believed that GMOs were safe, 32% were unsure and 36% thought that GMOs were not safe. After providing the information they found that 45% of people now thought GMOs were safe but that 12% more people thought they were not safe.

With regard to climate change 64% believed that humans were responsible for climate change, 18% were not sure and 18% did not think that humans were responsible. After information provision 50% of participants believed more strongly that humans are responsible but 6% went the other way; 44% were unmoved.

Whilst it is positive that people believing in the scientific consensus increased it is certainly disheartening that providing facts can push people further away too; although I'm glad that the positive side of the polarising effect was greater than the negative side. This is all important because it can help us learn about how best to communicate scientific research. I think for too long now science has been pushing the boundaries of knowledge further back but that scientists have failed to bring the public along with them. There will always be contrarians and crackpots, but if we're to show the public the fruit of our scientific labours then we need to get much better at understanding the effect we have on them.

To business, then. A few months ago researchers from the University of Florida wanted to see how providing scientific information changed people's minds on scientific matters. What they did was take a measure of people's opinions on several topics such as climate change and genetically modified foodstuffs. They were then provided with statements from scientific organisations like the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Examples of statements used are:

'To date, no adverse health effects attributed to genetic engineering have been documented in the human population'

'The scientific evidence is clear: global climate changed caused by human activities is occurring now, and it is a growing threat to society'

They then polled them again to see if and how their opinions had changed. On the matter of GMOs at the outset 32% believed that GMOs were safe, 32% were unsure and 36% thought that GMOs were not safe. After providing the information they found that 45% of people now thought GMOs were safe but that 12% more people thought they were not safe.

With regard to climate change 64% believed that humans were responsible for climate change, 18% were not sure and 18% did not think that humans were responsible. After information provision 50% of participants believed more strongly that humans are responsible but 6% went the other way; 44% were unmoved.

Whilst it is positive that people believing in the scientific consensus increased it is certainly disheartening that providing facts can push people further away too; although I'm glad that the positive side of the polarising effect was greater than the negative side. This is all important because it can help us learn about how best to communicate scientific research. I think for too long now science has been pushing the boundaries of knowledge further back but that scientists have failed to bring the public along with them. There will always be contrarians and crackpots, but if we're to show the public the fruit of our scientific labours then we need to get much better at understanding the effect we have on them.

Thursday, 13 August 2015

Golden Rant

There are a little over 7 billion people currently in the world, by 2050 there is expected to be 9 billion; all of them will need feeding but we don't yet produce nearly enough food to meet that demand. There are several ways we can try to square this circle; we can create more agricultural land by clearing forests or wetlands; we can change what we eat so that we eat less energy intensive foods, i.e. less beef, more chicken and grains; or we can try to force the land to give us more of a given produce per acre. The reality is that we'll probably end up doing all of these but one that I'm particularly interested in is producing more food from a given area of land, and specifically by using genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Attitudes to GMOs vary quite widely across the world but for some reason there seems to be a particularly strong resistance to the concept in much of Europe. France and Germany both have blanket bans, as do Austria, Hungary, Greece and Bulgaria and the Scottish Government has just recently come out against all GMOs. Other countries allow them but have such stringent regulations as to effectively ban them. Spain is a rare outlier where 20% of their maize is GMO. Even where it's legal any food set for human consumption must be labelled as GMO if it contains more then 1% GMO ingredients.

All this makes zero sense to me. The scientific case for the efficacy and safety of GMO food is now overwhelming. The argument against it consists of nothing more than an ad hoc mixture of anti-science/anti-intellectualism, a supposition that large biotech companies are somehow evil and the Natural Fallacy. To be clear, there is nothing 'natural' about the crops or animals we currently eat. They have been selectively bred for thousands of years to an extent that if you saw the original cultivars you simply wouldn't recognise them. If a man in tweed with dirt under his nails lets two animals get jiggy on their own all of their genes are mixing randomly, like shuffling a deck of cards; this is apparently okay and safe (which, indeed, it is). If a man in a white coat very precisely selects one gene with a specific function and splices it into the exact position in the genome he wants this is apparently a 'frankenfood' and will lead to the demise of the universe.

A case in point. There is a GMO called Golden Rice. It was invented by a pleasant man by the name of Ingo Potrykus whom I had the pleasure to meet whilst at university. He found a way to express the genes needed to make Vitamin A in the grains of rice. Understand that these genes are already present in rice but they are normally only expressed uselessly in the inedible leaves. This GMO is significant because Vitamin A deficiency is a huge problem in the developing world, especially in Asia where 500,000 children are left blinded every year. Potrykus teamed up with the biotech company Syngenta who invested heavily in developing ever better lines. The best performing crops, along with all relevant patents were then donated, for free, to the Golden Rice Humanitarian Project. The sole aim of this non-profit organisation is to give away, completely free of charge, seeds to the worlds poorest rice farmers who will be free to grow, harvest, sell on and reuse the seeds in whatever way they see fit.

It's a win-win, it really is. So it is especially galling to know that not one person has yet been helped by this new crop. It has taken well over a decade merely to get countries like India, Vietnam, the Philippines and Bangladesh to even allow trials to begin. This process has been fought tooth and nail at every step by organisations like Greenpeace who, to this day, continue to stand against Golden Rice. Their position is, frankly, despicable. Millions of children have been left to go blind because people in high places listen to scaremongering and ideology over logic and reason. This makes me sad. Fortunately, it should only now be a few more years until Golden Rice is approved in many developing countries and millions of people will very quickly feel the powerful benefit wrought by good science and genuine altruism.

Anyway, I appear to have gone on a rant instead of covering the article I wanted to mention; I'll come back to it tomorrow. And if you want to help, drop your local politician an email and tell them to listen to the scientists and start saving lives.

A case in point. There is a GMO called Golden Rice. It was invented by a pleasant man by the name of Ingo Potrykus whom I had the pleasure to meet whilst at university. He found a way to express the genes needed to make Vitamin A in the grains of rice. Understand that these genes are already present in rice but they are normally only expressed uselessly in the inedible leaves. This GMO is significant because Vitamin A deficiency is a huge problem in the developing world, especially in Asia where 500,000 children are left blinded every year. Potrykus teamed up with the biotech company Syngenta who invested heavily in developing ever better lines. The best performing crops, along with all relevant patents were then donated, for free, to the Golden Rice Humanitarian Project. The sole aim of this non-profit organisation is to give away, completely free of charge, seeds to the worlds poorest rice farmers who will be free to grow, harvest, sell on and reuse the seeds in whatever way they see fit.

It's a win-win, it really is. So it is especially galling to know that not one person has yet been helped by this new crop. It has taken well over a decade merely to get countries like India, Vietnam, the Philippines and Bangladesh to even allow trials to begin. This process has been fought tooth and nail at every step by organisations like Greenpeace who, to this day, continue to stand against Golden Rice. Their position is, frankly, despicable. Millions of children have been left to go blind because people in high places listen to scaremongering and ideology over logic and reason. This makes me sad. Fortunately, it should only now be a few more years until Golden Rice is approved in many developing countries and millions of people will very quickly feel the powerful benefit wrought by good science and genuine altruism.

Anyway, I appear to have gone on a rant instead of covering the article I wanted to mention; I'll come back to it tomorrow. And if you want to help, drop your local politician an email and tell them to listen to the scientists and start saving lives.

Wednesday, 12 August 2015

Sunspots And Climate Change Deniers

For over a week now Honolulu, Hawai'i, has been playing host to the 29th General Assmebly of the International Astronomical Union. Sadly this is not a precursor to Starfleet but it is still rather exciting nonetheless. The Union represents over ten thousand astronomers and the triennial meeting is always a wellspring of cutting edge space science.

On August 7th they released information about the longest continuous experiment in existence which dates back to observations taken by Galileo Galilei. It was all to do with sunspots. You see, from 1645 to 1715 there was what is sometimes referred to as a mini ice age; whist this is a factually poor description of what happened it is certainly true that winters were harsher during this period. This coincided with a prolonged trough in solar activity known as the Maunder Minimum and so it was that we have assumed for several centuries that the former was caused by the latter. Solar activity is measured by counting the number of sunspots visible on the surface of the sun at any given time: the more spots the more activity. More recent data, however, has started to contradict this hypothesis and so the whole model has come under increasing scrutiny.

This is significant because if solar activity has been steadily increasing for the past 300 years then it could go some way to explaining the warming of the planet that is such a pressing concern today. It would also mean that if the warming isn't anthropogenic (manmade) in origin then our various warnings about carbon emissions and heavy industry are incorrect. I know I personally have met people, let's call them climate change deniers, who say that us puny humans are incapable of affecting a whole planet in this way, and, that solar activity explains everything so it's fine to have a coal powered car built from amazonian mahogany. Well, the new data, which reconciles a long running discrepancy in the two ways we can count sunspots, shows that solar activity does not in fact correlate with the steady increase in global temperature that we have been observing since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. To quote them:

'[these results] make it difficult to explain the observed changes in the climate that started in the 18th century and extended through the industrial revolution to the 20th century as being significantly influenced by natural solar trends.'

Notice that there is wriggle room in that statement, but that is because it was issued by scientists who understand that new data can always change your theory. As it goes, that is actually quite a strong statement and would be a blow to the climate change deniers if their position was in any way based on reality. So there you have it, one more line of evidence to support anthropogenic global warming, one less place for the climate change deniers to hide. Will it change any of their minds? Not a chance.

|

| Hand drawn by Galileo himself this is one of a series of drawings that show the progress of sunspots across the surface of the sun with time. |

Tuesday, 11 August 2015

When You Wish Upon A Star

Asides from being useful for bringing inanimate puppets with a propensity for fibbing to life, shooting stars are also rather exciting to watch. This is just as well because we are about to hit the peak for the Perseid meteor shower. But what actually is a shooting star? Hale-Bopp; Swift-Tuttle; Halley's, these are all comets and comets all have something in common. Comets are effectively giant, dirty snowballs and as they sail around the solar system bits of water ice and rock and other debris stream off behind them, this is especially the case as thy warm up when they pass near to the sun. This cometary debris just sort of hangs about in the vacuum of space until an unwitting planet like ours happens to come piling through it.

A shooting star, then, is actually a tiny piece of comet that is entering our atmosphere and burning up as it does so due to the extreme heat produced as it drags through the air. The Perseid meteor shower is called such because the debris from the comet all appears to be entering the sky around about the constellation of Perseus. People much more clever and talented than I are able to take multiple images of Perseid meteors and overlay them, these combined images make it much more obvious what I mean when I say they radiate out of the Perseus constellation; see below.

Keeping the Greek theme going, comets are so called because back in the day the Greeks thought of the streaming tail of a comet as flowing long hair. Their word for that is κομᾶν which morphed into Κομήτης their word for comet, which my Greek buddy Anastasia reliably informs me is pronounced komiti.

The comet Swift-Tuttle, which I mentioned above, is actually quite pertinent here. It is the tail debris of this comet that we pass through every August which gives us the Perseid meteor shower, a phenomenon that astronomers have been observing for over two thousand years now. I was wondering if the meteor shower would diminish in magnitude each year as we slowly but surely clear the area of debris as we keep going through it, but then it gets replenished once Swift-Tuttle hurtles through every 133 years. I've struggled to find any information on this so I've tweeted a couple of proper astronomers to try to find out. I'll update this post if they get back to me.

In the meantime, if you're in the UK, look to the northeast in the evening and get some wishes ready.

**UPDATE: Astrophotographer extraordinaire and Sky At Night presenter Pete Lawrence got back to me about my theory and I'm totally wrong. The earth hardly removes any of the debris compared to how much the comet sheds and it does indeed replenish it as it orbits so, if anything, perhaps the Perseids will get more intense with time.**

|

| Image courtesy of NASA |

Monday, 10 August 2015

Polio Shmolio

Fantastic news, science fans! We are on the verge of extinctifying (definitely a real word) another species!! But don't feel blue, it's not a cute little rainforest critter or a beautiful tropical coral, it's the dreaded polio virus. Most of us in the west below a certain age won't really know what polio even is, that's because we all get vaccinated against it when we're babies and it doesn't exist here anymore. If you have an old person to hand and a spare four or five hours you can say the word polio at them and they will be able to give you a million stories about the terror that it used to instil in the population. Every street in the country had a child in a wheelchair left withered and paralysed by the disease, every hospital had a room full of iron lungs to help the most severely affected children breath and every neighbourhood had a grieving family.

Poliomyelitis, to give it its full name, is caused by an enterovirus only 30 nanometres in diameter. It is spread by the usual faecal-oral route and multiplies aggressively in your intestines; in some cases it will spread to your central nervous system and wreak havoc in the form of paralysis. There are three strains of the virus, simply called one, two and three; polio virus 2 was last seen in 1999, meaning we have already eradicated one strain from the planet.

In 1988 most western countries had successfully become polio free but it was still endemic throughout most of the world, indeed there were 350,000 cases in 125 countries that year. In 2014 there were 134 cases in just three countries; Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The reason I'm writing about this now is that Nigeria has actually just gone one whole year without a new polio case, an astonishing achievement given the difficulties they face there. For example, there were the usual African scare stories and propaganda about the vaccine supposedly containing the HIV virus; and, sadly, nine health workers were killed by Boko Haram militants two years ago for having the temerity to try to help people.

The massive, worldwide vaccination program that has given us this success has been spearheaded by the World Health Organisation, UNICEF, Rotary International and the US Centers for Disease Control. Together they have spent $10 billion immunising 2.5 billion children and the final eradication plan is to have the entire globe free of the polio virus by the end of 2018. Although there has been enormous success so far we must not get complacent. Polio only shows symptoms in 1 in 200 people and so the vast majority of cases wonder around quite merrily spreading the disease without ever knowing it. It is estimated that if just one child were missed and was left to spread the virus then within a decade we would be back to a level of 200,000 new cases per year.

It can be done, though; this wouldn't be the first time we have deliberately eradicated a deadly virus. In 1977 there was the last ever case of small pox; it now only exists in a couple of laboratories around the world. So there is hope, but the consensus seems to be that the last chapter is always the most difficult one. To ensure success a final push is being made to try to meet the 2018 target. Looking at their own timeline they seem to be about 12 months behind schedule so the end of the decade may be a more realistic target. In any case, when it happens it will be a huge success story for the planet and something that we as a people can be proud of; and it's all thanks to science.

Friday, 7 August 2015

Chicken Karma

As a die hard fan of curry I must admit that when I saw this open access article in the British Medical Journal it made my mouth water. Researchers in China have conducted an observational study which shows an inverse correlation between the consumption of spicy foods and mortality. People who ate spicy food on at least 6 days per week were found to be 14% less likely to die than those who ate it once or less per week.

They followed half a million people for 7 years and found specifically that those with a taste for spicy foods were less likely to die from cancer, ischemic heart disease and respiratory diseases; the effect was seen in both men and women.

As this is purely an observational study it is not possible to say that there is a cause and effect relationship at work here, indeed the authors were at pains to point this out. They did, however, control for age, education, sex, BMI, and everything else their data set allowed them to. They weren't fully able to control for socioeconomic status and this could certainly have an effect as, sadly, one of the strongest predictors of your health and wellbeing is the size of your bank balance. They also mentioned the possibility of reverse causality; perhaps people who are very ill and close to death avoid spicy foods.

So, no smoking gun, but there is a growing body of papers like these that show various protective benefits associated with the consumption of spicy food and it would appear to merit some more functional studies to try and isolate potential mechanisms. In the meantime, pass the poppadoms.

|

| Image used with permission |

Thursday, 6 August 2015

What Happens When The North Pole Becomes The South Pole?

A few days ago I wrote a post about the age of the magnetic field that protects us from the solar wind, it proved surprisingly popular, I hadn't realised geodynamism was such the hot topic. Well, here is a little more excitement for the earth sciences crowd.

Now, I don't want you to panic but since the year 1840 our magnetic field has been getting weaker and weaker at quite a fast rate. Fortunately, this won't ultimately lead to its complete demise but it is thought that it could lead to the north and south poles switching places Yup, that can happen. It's actually happened hundreds of times in the past and there is a consensus that it'll happen again soon, in this case soon means 1-10,000 years.

So should we be worried? Probably not. There are two main concerns about what might happen in the event of a pole switch. Firstly, it doesn't happen overnight. It is a gradual process that is accompanied by an overall weakening of the field for several millennia either side of the flip. Patches of the liquid outer core slowly begin to be polarised the opposite way and when enough of these patches exist the overall polarity of the planet will change. But it can be messy; as the field becomes ever weaker we might even end up with more than one north pole for a time. The concern arises because a weakened field removes much of the protection that I detailed in my previous post. It wouldn't be cataclysmic, as I said, this has happened plenty of times in the past; but large coronal mass ejections (CMEs) during this time could certainly punch a hole in the ozone layer which could have ramifications for skin cancer rates.

The second main concern would be for our precious electronics, they would also be more susceptible to CMEs. Much of modern life is highly dependent on satellites and we in the west wouldn't much like it if we lost portions of our main constellations.

What is completely unknown is how animals that rely on geomagnetism would cope. Pigeons, robins, whales, bees, salmon and many more all use the earth's magnetic field to navigate.

This is all relevant because a new article in the open source Nature Communications has shown that the current weakening in our magnetic field is not unprecedented. It is known that there is an area of very pronounced weakness in our magnetic field that stretches from Brazil, across the south atlantic and into southern Africa. Scientists have long assumed that, combined with the overall weakening of the past 160 years, this predicts an imminent flip in the field. This paper, however, shows that there was a significant weakening of the field about 700 years ago over much of southern Africa but it then recovered to normal levels. The decline, then, may not be terminal so no need to rush out and buy shares in sunblock manufacturers just yet.

|

| During a reversal the magnetic field is clearly drunk and should just go home. Image courtesy of NASA |

Wednesday, 5 August 2015

Tiger Numbers Dwindle

As yet unpublished research reported in the AFP has suggested that a survey of tigers in Bangladesh conducted in 2004 made a large error. By conducting a survey of paw prints it was concluded that there were about 400 individuals in the Sundarbans mangrove forest. A new survey used camera traps and is considered to be a far more accurate and reliable way of estimating the true number of tigers in the region. Unfortunately, the new number is only 106 and perhaps only as few as 83.

This is very bad news for what was already a highly threatened species. It now seems quite likely that bengal tigers will become extinct in the area in the next couple of decades. As a geneticist, it seems to me that even if something drastic happened and numbers recovered significantly they would still be in trouble. 106 simply isn't enough tigers to make a genetically successful population; they have reached a genetic bottleneck. If the estimated 3,200 tigers left worldwide were all in the same place and able to breed together then they might stand a chance, but they are split up into many very small sub-populations, geographically separated such that there doesn't exist a breeding population anywhere on the planet of more than a few hundred.

A century ago there were thought to be 100,000 tigers in the world, we have successfully wiped out more than 95% of them; there were nine subspecies of tiger extant, we've wiped out three of them. It would appear that their days in the wild are numbered but, as a species at least, they aren't in any real danger of going extinct. There are at least 5,000 tigers in the United States alone, all of them in captivity. But this throws up the question of whether or not it's appropriate to keep animals like tigers in captivity. Personally I don't think it is. I know this puts me in the minority but I would take samples, create a genetic ark and await a more enlightened time. Big cats and other large mammals in zoos do nothing but depress me. If you read the blurb on the side of an enclosure then it'll tell you that this all helps the conservation effort, but I've also seen information that seems to say that it does nothing of the kind and it is basically a marketing and merchandising scam. I assume there is an objective answer to this question somewhere, although I have no idea what it is. What does seem certain is that tigers in the wild do not have long left.

|

| Image used under creative commons license |

Tuesday, 4 August 2015

Ebola: A Vaccine

Ebola is a genuinely scary disease. After the outbreak in west Africa earlier this year there must be very few people out there now who haven't heard of it. It is a part of the haemorrhagic fever cluster of diseases, causes multiple organ fever and for you to essentially start leaking your insides out of every orifice you have. It is spread via contact with infected bodily fluids and results in death in about a half of people in most outbreaks, although the recent one had a mortality rate of 70% of those infected. It is a viral infection named after the Ebola river in the DRC near where the first outbreak occurred in 1976.

The current, now fading, outbreak has wreaked a terrible toll. 11000 people have died; normal life in entire areas of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia has been shut down. The seeds of fear and distrust have been sown in communities having a deep psychological effect that few people have even begun to try to understand yet. Now, though, for the first time, there could be hope. A vaccination has been produced by the Public Health Agency of Canada and a field trial has been completed, with promising results (published in The Lancet).

They used a strategy known as ring vaccination. This is where those in immediate contact with a symptomatic individual; friends, family, colleagues, neighbours; are vaccinated thereby forming a 'ring' of immunity around the test case. There were two groups in the study; group one was where all individuals in the ring were immediately vaccinated without delay; group two were also all vaccinated but only after a delay of 21 days. Previous, smaller trials had proved so effective that it was considered unethical to deny some people the vaccination.

In the second group, where treatment was delayed, there were 16 subsequent cases out of 3528 vaccinated. In the first group, that had immediate treatment, there was no cases at all out of 4123 people. That is a fantastic result for a vaccine that only began development a year ago; normally it would take a good decade to make that sort of progress. The trial took place in Guinea and now the powers that be are quickly trying to get through the red tape required to get the vaccine into Liberia and Sierra Leone. This might not be the end of the story, though; there are 5 species of ebola virus and we don't know how well the vaccine will work on each of them; we would also need to test more people to gain a fuller understanding of the potential side effects; and technically this isn't a licensed treatment yet, but everything is being done to smooth its path to widespread use. Plus, the vaccine has to be stored at -80 degrees Celsius, which isn't always an option in the poorly funded and equipped countries where ebola is prevalent. On the upside, GAVI, the global vaccine alliance, has pledged $390 million dollars to getting the vaccine to where it needs to be. There are also other vaccines in the pipeline which, together, may spell the end of outbreaks on the kind of devastating scale we have seen in the last year.

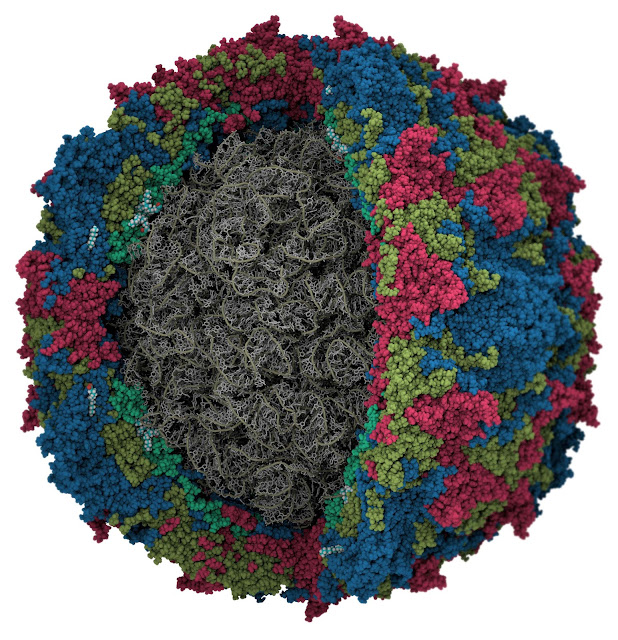

|

| Electronmicrograph of an ebola virion. Image courtesy of the Centres for Disease Control |

Monday, 3 August 2015

Why Living on a Giant Magnet is a Good Thing

One of the many things that is special about our planet is that we have a magnetic field surrounding it. On the face of it this doesn't sound so remarkable. So what? We can use a compass. Well, yes, but it is also one of the many factors that stopped us being a lifeless lump of rock floating through the endless, cold, uncaring void of space; it allowed us to be a living lump of rock floating through the endless, cold, uncaring void of space.

You may have heard of the solar wind, this is the stream of highly energetic particles released by the sun as it fuses hydrogen atoms together giving us our heat and light. But these particles could also wreak a terrible havoc if left unchecked. They're more than capable of stripping away our atmosphere and all the water on the planet without which there would be no life here, probably not even microbial life. Luckily for us many of the particles being churned out by the sun have a charge and can therefore be safely deflected by a magnetic field. Sometimes these particles get funnelled along the field to the poles of the planet where they can interact with the oxygen and nitrogen in our atmosphere, this is what produces the auroras borealis and australis.

Our magnetic field, also known as the magnetosphere, is a result of the molten iron outer core of the planet, it slowly rotates and acts just like a giant bar magnet in the centre of the world. It is thought that Mars used to have such an iron core protecting it from the solar wind too, but Mars is only half our size and its core wasn't able to maintain its heat and so solidified a couple of billion years ago. It's quite possible that until then there had been good conditions for life on Mars, but with the protective shield gone conditions became ever more harsh and it is now unlikely that any life survives on Mars (although we should definitely go there and double check).

And so to the point. A new article in Science has pushed back the age of our magnetic field by some half a billion years to approximately 4 billion years ago. This is important because it has implications not just for understanding the geology of the planet but also for understanding how life on earth involved.

The work involved digging up samples of some of the oldest known rocks on earth in the Jack Hills of Australia. These rocks have remained almost completely unchanged for many billions of years. Analysis of the magnetically aligned zircon crystals within the rocks can reveal whether or not those rocks were formed at a time when the magnetic field was in place. And so it proved to be in these 4 billion year old samples. This older age of our magnetic field means that there may have been conditions favourable for life here on earth much earlier than previously thought. Given that bacteria and archaea don't tend to fossilise well, and that there aren't many examples of rocks that are as old as that, this could be an important piece of information in putting a date on when life might have begun.

The work involved digging up samples of some of the oldest known rocks on earth in the Jack Hills of Australia. These rocks have remained almost completely unchanged for many billions of years. Analysis of the magnetically aligned zircon crystals within the rocks can reveal whether or not those rocks were formed at a time when the magnetic field was in place. And so it proved to be in these 4 billion year old samples. This older age of our magnetic field means that there may have been conditions favourable for life here on earth much earlier than previously thought. Given that bacteria and archaea don't tend to fossilise well, and that there aren't many examples of rocks that are as old as that, this could be an important piece of information in putting a date on when life might have begun.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)